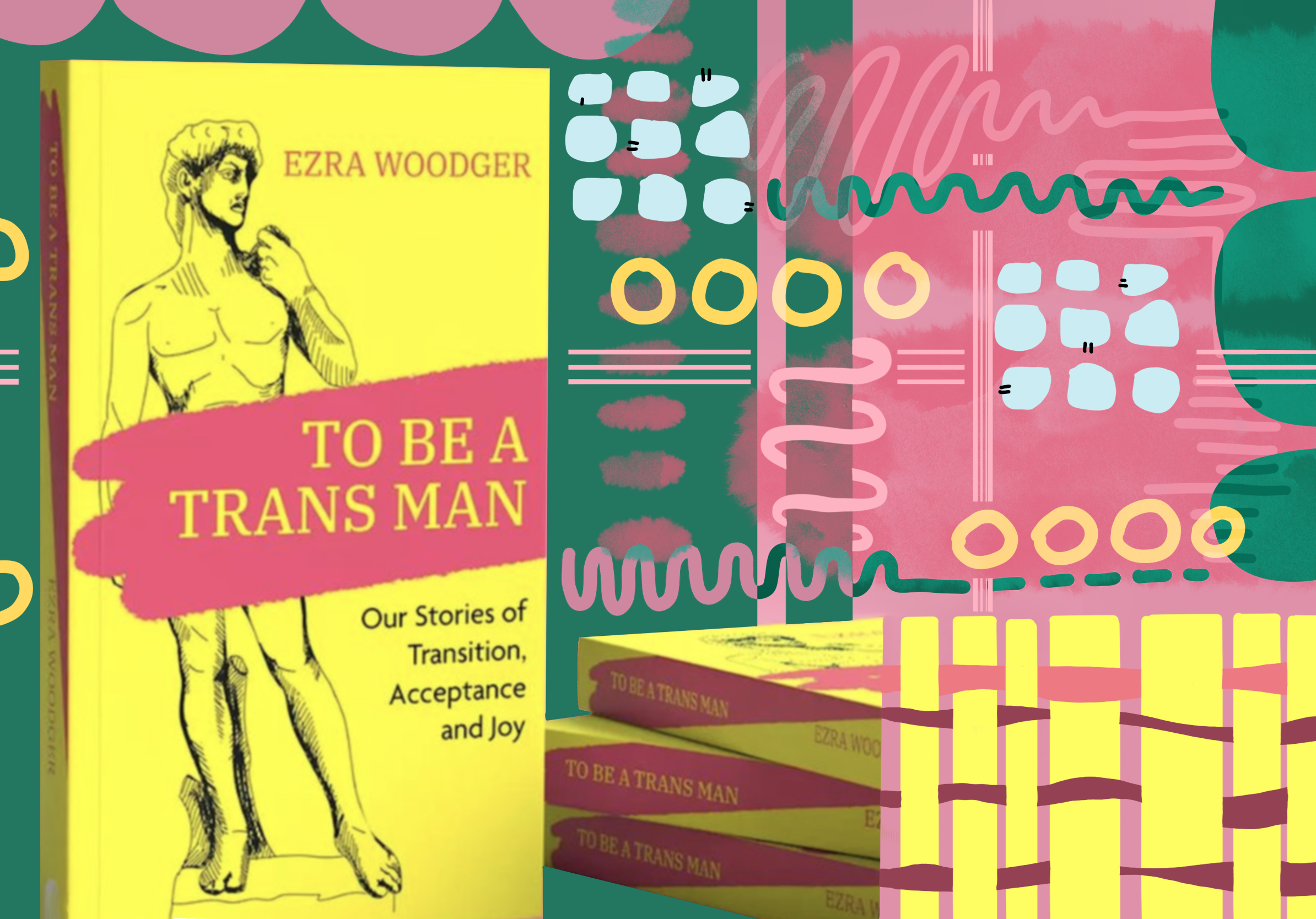

Mermaids’ Luan meets writer Ezra Woodger to talk about his new book, To Be A Trans Man

Ezra Woodger’s To Be A Trans Man was published earlier this month.

It is a refreshing exploration of trans men’s lives that asks, what is masculinity and how do trans men and trans masculine people experience and express their masculinity.

In the book, Ezra talks to eight trans contributors who share their views on masculinity and enter detailed discussion on a range of topics such as their experiences growing up.

There were a range of common themes spread throughout the book, one of which was “hyper-masculinity” experienced early on in transition.

This was important for me to read, helping me understand that I wasn’t alone with this experience and that I too could equally shift this expectation of myself in time.

What struck me following my conversation with Ezra was that expectations around expression as a gay trans man could equally cause you to box in your gender expression.

Discussions around individual perceptions of younger selves also took place. Casper Baldwin states in the book, “Your identity is not the thing that’s transitioning; it’s other people’s perceptions of it”. He goes on to say it “wasn’t a girl thing, it was a me thing”.

This sentiment was healing. It gave me immediate comfort to know that my younger self was valid in how he lived and survived.

Additionally, Leo George talked about his experiences of being a disabled trans man and discussed the gender ambiguity that occurs when sat in a wheelchair.

This was something I’d never thought about as a disabled trans man myself and it surprised me.

After reading To Be A Trans Man, I spoke to Ezra over Zoom.

How would you describe the book and its importance?

Ezra: I think I’d describe it as a love letter to trans masculinity.

When I set out writing the book, I wasn’t sure what it was going to be, but I knew I didn’t want it to be a self-help “How to be a man” type of thing.

It became clearer as I was writing it that that was utterly impossible to do because we’re all so different.

So really, I think it’s specifically a love letter to masculinity and trans masculinity, more so than anything else. It didn’t teach me how to be a better man, but it gave me an appreciation for how we exist as men.

The book talks a lot about the pressure put on trans men compared to cis men in terms of masculinity, which I don’t think I’ve seen talked about. Can you say more about that?

I think cis men are given the luxury of the process of experimentation – they are allowed more of it.

If and when trans men start to experiment more with style or fashion or just the way we express ourselves, it’s almost like people are looking for proof that we’re being inauthentic or faking it.

The way we express ourselves – masculine or feminine – isn’t really any different to how cis people do it. But trans people are more likely to be scrutinised for the way we express our gender. It’s getting better but I do still feel the pressure to kind of “masc-it-up” in certain spaces to be taken seriously.

Which creates a difficult and upsetting balance to try to strike between getting taken seriously and sacrificing something, or you risk people questioning you, and depending on how much energy you have, it can be difficult to deal with.

What was the most surprising thing you heard from the guests in your book?

Ooh, that’s a really good question. I think I was surprised when Ezra Michel was talking a lot about his past and his journey to where he is now.

He’s a super talented creator with this aura and charm, but he also talks very honestly in the book about how he used to struggle with addiction and was once married. The stark difference between that and the person he is now was surprising.

It highlights this kind of capacity for growth which we all have.

The book talks a lot about representation – good, bad, and the lack of it. Do you have a favourite piece of trans representation in the media?

I will always talk about Cemetery Boys by Aiden Thomas. I think it’s a fantastic book and you can really tell when it’s a trans person creating the art.

His trans identity is important in the book but he doesn’t feel at war with himself and there’s no kind of internal struggle. It’s brilliant – everyone should read it. His new book, The Sunbearer Trials, is coming out and I’m very excited.

I think it’s important to have representation that is a kind of catalyst for things to happen, but it isn’t all that happens, which is an important distinction to make.

For me, for representation to be meaningful, being trans needs to matter but it isn’t the driving force and it’s not the conflict or the struggle. It’s just an important facet of the story.

Coming away from the book I felt a sense of calm, peace, and joy. Why do you believe it’s important to centre joy in the trans experience?

That’s a really good question and something I didn’t expect to want to centre as much. I knew I didn’t want to focus on how sad we are a lot of the time, but I think that the “joy is the answer” message that I came to, came from talking to all the different people and realising that what helped our masculinity – and even helped figure out we were trans – was joy.

A lot of us didn’t figure out we were trans from dysphoria – we all felt terrible as children, but we didn’t have the words to express why. In fact, it was the process of being affirmed and seeing what life could be like that gave us that, “Ah, this is it” moment.

So, I think joy and euphoria has always been the answer. I kind of roll my eyes at myself a couple of times in the book because I was being so sappy and sentimental, but I think it is that joining together, finding each other and community, that means we are left with joy. Sometimes what else do we have other than that to hold on to?

What would you like people to take away from your book – in particular young trans people?

You don’t have to put so much pressure on yourself because it can be really, really difficult.

It’s getting better – it’s a lot better than when I first realised I was trans and was in the process of coming out. There are more resources and there’s more support available and that comes with its own issues which we are currently seeing.

But I think it’s still difficult to navigate what it all means and “how to be trans”, as it were. What does it mean to be a trans person? And a trans man specifically?

I want to be clear that you don’t have to put so much pressure on yourself. The support is there, and in the community, we do have each other’s backs – the queer community exists for a reason. There’s no need to do all of this on your own.

—–

When I read the book, I came away with goosebumps and near tears from the beauty and peace within these pages. Ezra concludes joy has always been the answer and I think he’s right. There’s so much joy in being trans despite the hardships, living true to us and feeling euphoria has always been joyous which is celebrated throughout the trans and queer community.

To Be A Trans Man is an essential read for all trans masculine people especially trans teens. Rico states in the book “We’re standing on the shoulders of giants” who have paved the way, fought for us, and rallied to uplift our voices.

You are safe and welcome in this book to live, express and thrive as men or non-binary people however you see fit.

To Be A Trans Man by Ezra Woodger is out now. Please support his great work and grab a copy!